As incredible as it may seem, we have another recent development relating to the stream crayfish of the Ozarks. First, all of our stream crayfish were moved from the genus Orconectes to Faxonius. Now we have two new species!

Fetzner Jr, James W., Taylor, Christopher A. (2018): Two new species of freshwater crayfish of the genus Faxonius (Decapoda: Cambaridae) from the Ozark Highlands of Arkansas and Missouri. Zootaxa 4399 (4): 491-520, DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4399.4.2

In a study published about a couple of weeks ago, Doctors Fetzner (Carnegie Museum of Natural History) and Taylor (Illinois Natural History Survey) split Faxonius eupunctus into three species. F. eupunctus was not a species I expected to be split. It is (or was) limited to three adjacent drainages and I’ve never noticed any difference in the specimens I’ve observed. For what it’s worth though, I wasn’t expecting any differences and that lack of expectations may have kept me from noticing anything.

After I saw the title of the study, but before I read the abstract, my first thought was that F. neglectus had been split again—a split into at least three species had been proposed several years ago, though that doesn’t appear to have been adopted/accepted. Nor would I have been surprised if it were one of the species that is widespread in the Ozarks and varies greatly in appearance from drainage to drainage (F. luteus, F. punctimanus, F. ozarkae.)

But no, F. eupunctus it is. The new species are named F. roberti (in honor of Robert DeStefano of Missouri Department of Conservation) and F. wagneri (for Brian Wagner of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission). The suggested common names are Spring River Crayfish and Eleven Point River Crayfish respectively.

F. eupunctus (formerly) occurred in the Eleven Point, Spring and Strawberry Rivers of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. When I saw that they had been split, I was expecting that they simply separated the populations of each of those three rivers into distinct species. I should be so lucky.

The population that occurs in the Spring and Strawberry Rivers was split and is now known as F. roberti. That’s the easy part. Once you get back to the Eleven Point, things get trickier.

F. roberti, October 20, 2010, Barnes Road Bridge, Strawberry River, Sharp County, Arkansas.

F. eupunctus is now restricted to the Eleven Point, but F. wagneri also occurs in the Eleven Point, though they specified the 54-mile stretch from Greer, Missouri to Birdell, Arkansas. F. eupunctus also occupies that stretch of the Eleven Point but extends upstream of Greer at least as far as Cane Bluff Access, probably further. Therefore, over most of F. eupunctus’ range and all of F. wagneri’s range, the two species occur together.

To further complicate things, you have to get into the weeds to differentiate between them. Let me quote the study on how to separate F. wagneri from the other two (we don’t have to worry about F. roberti since it doesn’t occur with the other two):

Faxonius wagneri can be differentiated from both F. eupunctus and Faxonius roberti sp. nov. by using the male Form-I and Form-II gonopods, the shape of the chelae, and the female annulus ventralis. In F. wagneri, the terminal elements of the first pleopod are almost twice as long as those in F. eupunctus and F. roberti, with the tips of the appendage reaching the posterior base of the first perieopod when the abdomen is flexed forward, whereas, in the other two species, these elements only reach the base of the second pereiopod. The species also possesses two spines on the dorsal side of the merus of the first pereiopod, which helps distinguish it from F. eupunctus.

Clear as mud, right? I’m sure that any astacologist knows exactly what it means, but I’m out of practice (that’s my story and I’m sticking to it) and had to take some time to decipher it. I don’t know that I’ll ever be able to use any of that to make a positive ID in the field.

Let’s unpack things and see where we stand. Gonopods are a pair of swimming legs that have been modified for sperm transfer and come in two forms, one that is capable of reproduction (Form I) and one that isn’t (Form II).

A male crayfish typically molts into Form I in the fall and back to a Form II in late spring/early summer. The Form I gonopods are widely used to distinguish between similar species, but you must have the crayfish in hand, it must be a male (obviously) and you either need very good eyes or a magnifying glass of some sort.

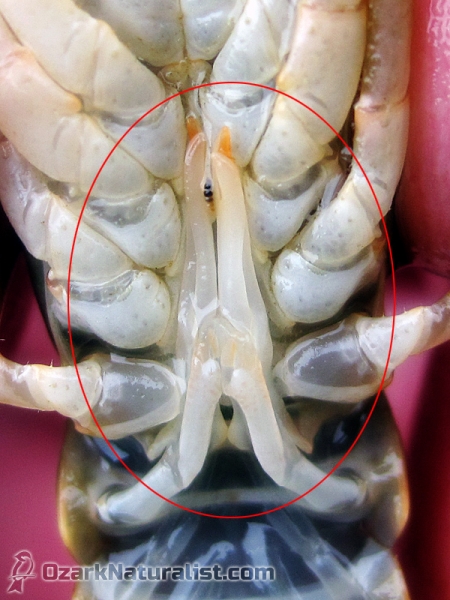

Form II Gonopods (from an F. luteus)

The chelae are the claws, which are clearly visible in most photos. But unless I missed it, the study doesn’t clarify how the chelae actually differ between the two species. For the time being at least, that’s not a viable way to make an ID.

The annulus ventralis is the female crayfish’s sperm receptacle. Here again, you’re going to need the crayfish in hand before it’s of use in making an ID.

This image is from an ovigerous female photographed at Greer Access in January 2013 and identified at the time as F. eupunctus. Unfortunately, I find that comparing the photo with the annulus ventralis images in the study to be inconclusive. The top half looks more like F. wagneri, but the lower part more like F. eupunctus (look at the seam in the middle.)

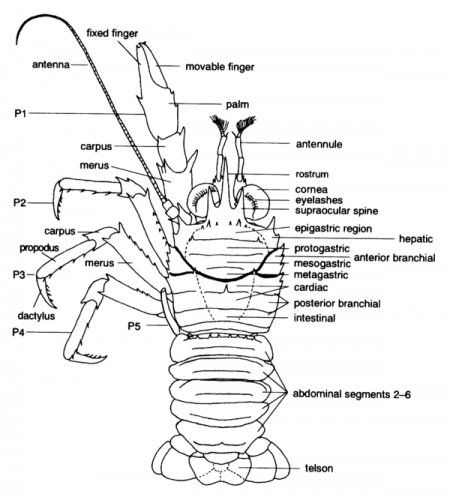

Pleopods are the swimming legs and the first pair is modified into gonopods, while pereiopods are the walking legs, including the pair with the claws. So, this is describing the details of the gonopods and we addressed those a couple of paragraphs earlier.

The merus is a segment of the cheliped (the walking leg that ends in the claw), the second from the claw.

Source: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Dorsal simply means the top side, so we’re looking for spikes on the top side of the second leg segment back from the claw.

These merus spines are the most promising feature for use in making an id in the field or from a photo. F. wagneri has 2 spines in 88% of specimens examined, while 81% of the F. eupunctus specimens had a single spike. Those percentages leave room for doubt but would allow at least a well-educated guess.

I’ve gone through photos from the Eleven Point that I had originally identified as F. eupunctus and found that I can sometimes distinguish the number of spikes. Based on this, I’ve apparently found and photographed both species in the past, though as we established above, the spikes can’t really give you an absolute ID, just a strong “probably.”

You can get a clear view of the spikes (or rather spike) on this crayfish, so that means it’s more than likely an F. eupunctus. On the other hand, the crayfish in this next sequence has two spikes so the odds favor it being an F. wagneri.

The five photos above were all taken in the same location (1 mile downstream from Greer Access) on the same day. The F. eupunctus is much darker and more greenish than the F. wagneri, but I think that this fits within the normal range of variability. I’ve seen crayfish that I believe to be F. eupunctus which were colored very similarly to the F. wagneri above. For example:

F. eupunctus, June 19, 2011, Cane Bluff Access, Eleven Point River, Oregon County, Missouri.

So I don’t see how coloration can be used to distinguish between the two species. I’m anxious to get back to the Eleven Point and put in some time looking at crayfish to see if I can get a better handle on identifying them.

An important thing to keep in mind is that F. eupunctus was already on Missouri’s Conservation Concern list. In fact, the species was beginning to receive attention as a possible Endangered Species candidate, which led to this study. Now that the species has been split into three, each population is, of course, smaller and more range restricted than the original.

This only increases the vulnerability of each. All three will undoubtedly be placed immediately on the Conservation Concern list if they aren’t already. And if F. eupunctus alone was being considered for Endangered Species status, the split should make all three candidates.

This is especially true since F. neglectus has been introduced into both the Spring and Eleven Point watersheds. F. neglectus chaenodactlyus, native to the adjacent North Fork drainage, is well established in the West and South Forks of the Spring River and appears to be displacing F. eupunctus (now F. roberti).

In the Eleven Point, the Missouri Department of Conservation discovered a population of F. neglectus neglectus in Jolliff Spring Branch on the Barren Fork, in the upper reaches of the drainage. F. n. neglectus is native to the Spring/Neosho River basin. F. eupunctus has only been recorded from the lower reaches of Barren Fork, though it occurs throughout the main stem of the Eleven Point (this is some 15 miles upstream of the described F. wagneri range.) At the time of the report (2011), the invasive population hadn’t yet come into contact with F. eupunctus. But it’s likely only a matter of time until this occurs if it hasn’t already.

A friend of mine tends to get irritated when species are split, believing it to usually be unnecessary. But this is a good thing from my perspective. It gives me a crayfish project to work on, something I’ve been without since I finally met my goal of photographing all the stream crayfish of the Ozarks. As I said before, the Eleven Point is close at hand, so I expect I’ll be making a few trips down there before long. All you crayfish better hide your genitals.

References:

Crandall, K.A. & De Grave, S. (2017) An updated classification of the freshwater crayfishes (Decapoda: Astacidea) of the world, with a complete species list. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 37 (5), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/rux070

DiStefano RJ, Imhoff EM, Swedberg DA and Boersig III. TC (2015). An analysis of suspected crayfish invasions in Missouri, U.S.A.: Evidence for the prevalence of short-range translocations and support for expanded survey efforts. Management of Biological Invasions 6(4):395–411.

Fetzner Jr, James W., Taylor, Christopher A. (2018): Two new species of freshwater crayfish of the genus Faxonius (Decapoda: Cambaridae) from the Ozark Highlands of Arkansas and Missouri. Zootaxa 4399 (4): 491-520, DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4399.4.2

Imhoff, E.M., Moore, M.J. & DiStefano, R.J. (2012) Introduced alien ringed crayfish (Orconectes neglectus neglectus Faxon, 1885 ) threaten imperiled coldwater crayfish (Orconectes eupunctus Williams, 1952) in the Eleven Point River drainage, Missouri, USA. Aquatic Invasions, 7, 129–134. http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/ai.2012.7.1.014

Larson, E.R. & Magoulick, D.D. (2008) Comparative life history of native (Orconectes eupunctus) and introduced (Orconectes neglectus) crayfishes in the Spring River drainage of Arkansas and Missouri. American Midland Naturalist, 160, 323–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1674/0003-0031(2008)160[323:clhono]2.0.co;2

Magoulick, D.D. & DiStefano, R.J. (2007) Invasive crayfish Orconectes neglectus threatens native crayfishes in the Spring River drainage of Arkansas and Missouri. Southeastern Naturalist, 6, 141–150.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1656/1528-7092(2007)6[141:icontn]2.0.co;2

Pflieger, W.L. (1996) The Crayfishes of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City, pp. 152.

Rabalais MR, Magoulick DD (2006) Is competition with the invasive crayfish Orconectes neglectus chaenodactylus responsible for the displacement of the native crayfish Orconectes eupunctus? Biol Inv 8:1039–1048